At the end of this post is an excerpt from the story ‘Black Prince‘, the first story in Stories Of An Awkward Size.

Mystery stories grip me, and for me it’s all about the reveal.

I don’t mind if the solution to the baffling goings-on is one I’ve seen before. I just don’t want to see it coming – or if I do see the punch-line coming, I want to be pleased to welcome it!

For me, Science Fiction and Fantasy are at their very best when they are Mystery stories.

O’Bannon’s Alien creature – what horrific morph is the ‘morph going to pull off next? Doctor Who’s The Face Of Evil – how is it possible that the adversary has the good Doctor’s own voice? Lev Grossman’s The Magicians – from whence did The Beast suddenly spring, and what is its gruesome agenda?

In Donny Darko who is the mysterious “Frank” that Jake Gyllenhaal’s hero keeps …

Ah yes, that last one. It brings me to a particular word.

Slipstream.

What is this Slipstream?

Well, let me have a go at explaining this word, this “meta genre” (though I feel I should do an entire blog post one day just dedicated to it).

Slipstream. It’s a term coined by Bruce Sterling, it means different things to different people even though there is a “rough consensus”, and it’s a subject of violent arguments vigorous debate.

Let me try a quick summary.

To me Slipstream is fiction that (1) is Mystery, ie. it contains a central mystery, and (2) has an ordinary, everyday reality (which does not have to be now or here) that is totally bent out of shape by one or two parameters going out of whack.

Thus Slipstream doesn’t necessarily have to be fantasy or science-fiction. Its source or drive can be any weirdness you like, the weirder the better – though in my rulebook you had better write a good story to go with your weird, any fool can come up with a non sequitur!

Gone Girl, both film and novel, I feel is a good example of non-fantastical Slipstream.

Looking back in time, I’d have to call Roald Dahl’s Tales Of The Unexpected, and Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone, among others, the modern origins of Slipstream.

You get the idea?

But let’s talk about Slipstream in the context of Science-fiction – in particular hard Science-fiction, where the physics and set-up really matter.

If you haven’t seen Charlie Brooker’s magnificent anthology series Black Mirror, I cannot recommend doing so highly enough. It is pure Slipstream, at least from my viewpoint, and even though some episodes are deliberately larger-than-life (like the superb Fifteen Million Merits, starring Daniel Kaluuya) it is also mostly hard-SF.

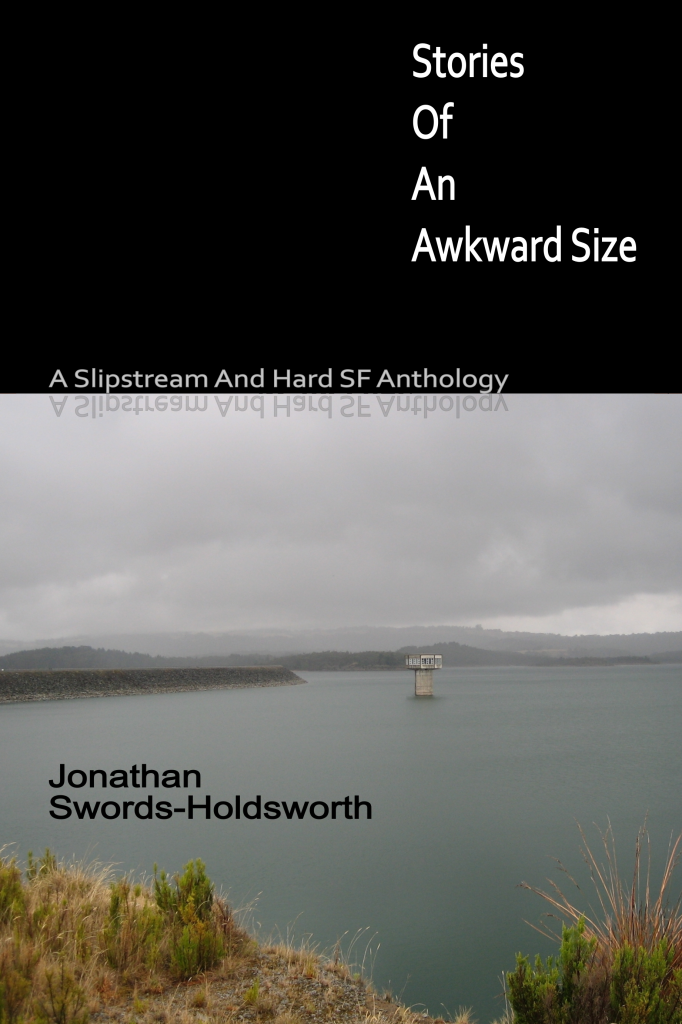

And this brings me to describe my first tome, Stories Of An Awkward Size: A Slipstream And Hard SF Anthology.

I like Mystery, remember? But I like tales of the real world. The real world does far, far weirder things than … well, pretty much any fiction I have ever read. That’s my take.

Robot jockeys in the Middle East. Airships almost a kilometre long and lit by green light, pulled nearly vertical by night storms over the Atlantic. A genetic condition that turns your urine blue and sends you mad, temporarily. A fish with a completely transparent body and eyes looking out from the middle of its head. Two black holes, with a combined mass sixty times that of our sun, colliding and merging in less than a third of a second …

Those are (or were) all real things, and so too are an infinity more.

Don’t get me wrong. I like Space Opera when it’s done right – I’m a big fan of Firefly and BSG. I like Fantasy when it’s done right too – I mentioned The Magicians before, and I eagerly await the next season of Game Of Thrones. And you know I like Mystery, including the “traditional” kind – big Elementary fan here!

It’s just I’ll leave those to others to write.

I want to write about things that might be, about the what if’s.

That said, please allow me to be a hypocrite – I do have Fantasy and Mystery strings to my bow, and I’ll be pushing some of those stories out the pipe at a later date. They will still be Slipstream, though (or I’ll certainly try).

But Stories Of An Awkward Size is strictly hard-SF (and yes that includes the rather abstract Mr Devries’ Red Bowler Hat, for those who were asking!), but the stories describe mysteries in which reality, in some way, gets bent all out of shape and everything just gets weird. Slipstream.

So that just leaves one thing. What’s with this “awkward size” business?

Well, the book is five novellas, or “long stories”.

I write to the length of the story. If it’s short it’s short, if it’s long it’s long. I am firmly against padding.

To write a very long story, generally speaking – ie. a novel, and I’m working on one of those currently – one has to weave two or three threads (or a lot more) around each other, so that you are actually telling several stories at once. They are just connected loosely to each other, like the spines of DNA molecules linked by the gentle hydrogen-bonding of base-pairs …

These five stories are singular stories, each one making its own individual point. Thus, their arcs follow their natural course, and they are the length that they are.

But hey, I write flash-fiction too, so stay tuned for some of that ultra-short goodness!

Stories Of An Awkward Size is also the first of a series of Slipstream and hard-SF anthologies, all of which will have Awkward somewhere in the name. The stories are waiting in the wings to be done, edited and packaged up into volumes. (The next book in the series will probably be titled Awkward Continuities, but I’m not sure yet.)

Oh, the subjects of Stories Of An Awkward Size?

Hmm, ok, without blowing any plot details, try …

The afterlife, immortality, bio-tech, virtual reality, future weapons, graffiti, drones, artificial intelligence, hypersonic jet-liners, Japanese performance-art and more.

That do?

Below is an excerpt (with paragraph breaks provided by WordPress) from ‘Black Prince’, the first story in Stories Of An Awkward Size. Enjoy!

![]()

Black Prince

Henri Roseboro looked up from his computer, and realised the day was ending. The clouds were salmon, seen through the garland of plastic fruit hanging from the window. He rubbed his eyes.

The fruit were a reminder of Jena, his ex. She had hung them in the first month after they moved in, and then she had left him at the end of that same month. They had rented the house – intended to be their long-term home – three months ago.

Three months.

Henri couldn’t believe it.

The breakup had happened – the rent subsequently doubling – and then he had discovered that there had been, less than a year before, the violent and unsolved rape of a tourist in the back alley.

Altogether his feelings for the house, indeed for the whole neighbourhood, were now utterly soured – he wanted to leave it all and move on. But he kept procrastinating.

Concentrating on work was almost impossible, but on stopping his mind filled with thoughts of Jena, and what might have been. He really needed a third option now: something he could feel passionate about – or that could just distract him.

Henri gazed out at the sky, admiring it. Global Warming was far from under control; the city’s cloudscapes were becoming wilder, especially near dusk. He loved them, really. One day, he thought, when responsible governments finally appeared and repaired the atmosphere, he would miss these shapes. Perhaps by that time he would be living somewhere else, even under a different sky altogether.

He stood up and stretched, pushing his chair aside. Figuring contractual obligations could go on hold, he decided to enjoy something of the outside spectacle. He headed through the kitchen, out the back door, and across the rental’s tiny courtyard.

There were reminders of Jena here, too. The hanging pot-plants and huge ceramic bowls, rain filled, had been part of her grander plan. For the hundredth time he thought he should get rid of them, but he feared the stirring of feelings the task would provoke – he hadn’t quite crossed his mental and emotional Rubicon; not yet.

He paused and unlocked the alley gate, stepped down onto the cobblestones, and felt better. This alley was his, her memory was banished from it. He visited it at many a failing light; he had since moving in.

The alley commanded a view of fences, trees and vines, and above them all a jumbled skyline, now soaked in the deep, pastel onset of dusk. He scanned up and down the lane, enraptured with the way the streetlight advanced as the sky dimmed. It pushed and manipulated the creeping shadows, obliterating some, darkening others.

Not a decade before, the done thing in such a repose would have been to light a cigarette, but this was a somewhat rarer phenomenon these days. For Henri, just the alley and the light was stimulation enough. He waited now, as always, until the surrounding darkness deepened. For this was when the real show started – when the sky brought up its bloody reds, intense blues and subtle greys.

Opposite his alley door was a white wall, on the back of something brick that once might have been a garage. This had amazed him since he had moved in – how on earth had it remained unsullied, in this age of scribble? Henri was grateful for this clean white wall’s existence: in the dusk, it made a perfect colour canvas. Beyond the wall, in the distance, was a two storey house, a glow of fluorescent tubes illuminating its windows. Henri thought it was all art.

He noticed a movement out of the corner of his eye. He looked down and beheld the shadow of a cat, moving on the white of the wall.

“Heh, Kitty,” he said aloud, turning and searching for the original. He scanned along the top of his fence.

There was no cat.

Damn things move too fast, he thought, and looked back at the wall.

The shadow was still there.

He looked back at the fence, then again at the wall in a double-take. Still there was no cat, anywhere. And now he realised – there was no angle that could have put a cat’s shadow on the wall. Not in that way.

Fear. A pulse of it hit him, surprising him and leaving him breathless. An icy chill had crept down his back and he felt his hair standing up, his heart pounding. In the back-room of his mind a voice had whispered. Ghost.

He took a step back from the wall. The cat shadow paced, then doubled back and stopped, its tail swishing above it.

Ok … he thought, it’s just a … cat. It’s not something to run screaming from? Right?

He stared at the patient shadow, then checked one more time that he wasn’t being fooled by the streetlight and a furry … it was a cat’s shadow, all by itself.

The rushing of blood in his ears quietened, and he felt common sense returning. With it came the pull of curiosity.

He took a conscious breath, then paced slowly over to the fence, just to the right of the wall. He got in close to it and looked down. The cat shadow was vertically compressed from this angle, but he could see it looking “up” at him. Expectantly? he thought.

Henri knelt by the edge of the white, and looked the phantom in the eyes. Except there were no eyes – it was a solid, black silhouette. He leaned in and squinted at the shadow’s outline. The apparition made this difficult by shifting about like … like a cat – the creature’s body-language was uncannily accurate. Organic.

It took a few moments of careful inspection, before he finally saw the prank that had been visited upon him. He breathed deeply, surprised at how tense he was from the encounter. The cat shadow’s edge was furry, complex – detailed, he thought – but even so, he now made out a fine grid of blacks, greys and whites.

It was pixelated. He was looking at a screen.

He took a few steps back and gazed at the wall. Then he swore.

“You gotta be kidding me …”

Over the last decade or so, city councils and district governments, the world over, had gained a new plague to do battle with.

Graffiti.

But this was not the spray-paint and stucco of old, it was the thing in its newest incarnation. The technology of surfaces had come a very long way, and like all technologies it had rapidly spread from the lab to the street.

A war of escalation had broken out across a battlefield of walls, leaving applied-science fallout in its wake – locked surfaces that couldn’t be painted on (except with chemically keyed dyes), images that were invisible (except in the correct light), animations (one of the new technology’s earliest tricks) …

And the most interesting and powerful innovation of all: active surfaces – the spray-on device. Utilising special application-equipment and self organising materials, there were now spray-on cameras, sensors, speakers – even computers. You could have anything you wanted, overlaid on any facade – as long as you were prepared to pay for it, of course.

Henri whistled to himself. The stuff was called Graf, and this had to be two or three thousand dollars worth of it, perhaps more.

On a dead garage wall, in a back alley.

Henri got in close again, but this time near the centre of the wall. The sky was now dark enough that his own streetlight-shadow was nearly solid on the white. It wasn’t aligned the same way as the cat’s, but flat silhouettes without defining cues (like eyes) are forgiving of errors of perspective: to Henri it seemed, convincingly, like the cat and he were sharing the same two-dimensional plane.

He crouched down level with the apparition again, bringing his own shadow down with him. The cat wandered aside and back again, getting clear of Henri’s outline – almost, he noted, as though the creature found it to be a physical obstruction.

“Flat Cat?”

He saw that his shadow was still fainter than the cat’s, which by contrast – literally – was jet black. Experimentally he reached out with his shadow hand, and was jolted again: the cat shrank from his shadow’s appendage, then came back, sniffing at it. Henri had met enough cats to recognise the protocol. He shadow-reached behind the cat’s ears, to scratch. The cat arched, and Henri could see his phantom finger-tips flattening and releasing its ears. There was no sound, but in his mind he imagined purring.

“Well, Flat Cat,” said Henri, both amused and astonished, “I wonder who made you?”

He had an idea and stood up, the cat recoiling at the movement.

“Ok, you’re a shadow cat. So, do you eat shadow food I wonder …?”

As he backed away and turned toward his gate, the cat’s head followed his shadow across the wall; its tail flicked.

He raided his courtyard and retrieved a flower-pot base, brushing it off. He brought it back to the alley, expecting the cat to be gone. But it was still there, patiently waiting.

Henri noticed something. With his own shadow now off the wall entirely, the cat appeared to be looking directly at him. He remembered too how it had behaved when it first appeared; now he realised what it meant.

It can see, he thought, it can actually see.

He placed the bowl on the ground against the wall, noting that it cast a strong shadow. The base of the wall had a broad, raised lip, and because of it the new object ended up neatly placed inside the cat’s planar realm. That, Henri thought, had to be deliberate.

The cat padded over, looked at the bowl and pawed it. The bowl’s shadow shifted, and Henri felt another jab. He leaned down and kept his eyes on the bowl, until they grasped how the wall had tricked them. The surface had filled in the bowl’s shadow, with the same jet black as the cat. He pondered on it, that the bowl had … passed into the Graf. It had been recorded.

The cat was not impressed with an empty bowl, and assumed a quizzical pose. Henri leant further, and picked the pot base up again. As he lifted it, the Graf shadow followed the bowl’s real one, barely a centimetre behind. He was hypnotised.

He raced the bowl back into his yard, and searched again. Squatting down, he picked up a handful of mulch and carefully sprinkled it into the vessel. The mulch made a small pyramid in the centre of the dish, projecting an inch or so above the rim.

He returned and placed the bowl where he had before, satisfied to see the mulch become clearly visible as a black peak in the Graf. The cat walked up to the bowl, sniffed it, and at once began eating.

Henri squatted down and watched, slack-jawed. As the cat took bites, the Graf shadow of the “food” began to disobey its physical counterpart. The peak disappeared, bite by bite. The mulch pile’s real shadow remained, but the deep, deep black of its mirror image outranked it. In a few bites the cat had finished, and the peak was gone from the bowl’s shadow. The cat retreated a metre or so away and sat down, then began grooming itself.

Henri had not dared disturb the scene while the shadow was eating, for fear of what it might do to the simulation, but now he grabbed the bowl. He carefully straightened up, holding it before him and keeping his eyes on the Graf. The empty bowl tracked the full one, as perfectly as before, yet the mulch peak remained invisible to it. He turned the bowl upside-down, emptying the mulch onto the cobblestones. The falling material’s fainter shadow didn’t seem to matter: the Graf bowl remained empty, and there was no falling Graf copy of the shower of woody material. Henri stood with the empty bowl by his side, staring at the preening shadow.

Suddenly the cat perked up and froze, looking to stage-right, with its ears vertical. Henri instinctively looked in the same direction, and squinted.

He could see distant human figures in the gloom, coming towards him up the alley. A moment later he could hear their faint voices.

He looked at the silhouette.

“My gods, you can hear like a cat too …”

The shadow bolted, running to the right and … off the wall: a cartoon, thought Henri, defying the edge of the film. He beat a retreat back into his yard, then hid near the fence and listened. If the cat decided to appear for these gate-crashers, he would wander out and introduce himself. Heck, he might even make some new friends.

But as he waited the next minutes out, the intruders – it sounded like three – wandered past and kept going, laughing and chatting among themselves. Henri was fairly certain that if a shadowy cat had manifested, it would have been a talking point.

When the voices had faded to nothing, he ventured out into the alley again.

“Puss puss?”

But the cat did not reappear.

He was disappointed, but he decided it was time to return to the warmth and comfort of the interior anyway. As he locked the gate and turned away he was feeling a smugness, thinking about the tale he would tell.

It lead him to an epiphany, arresting him in mid-stride.

He reflected: his must be the same cycle of thoughts that everyone who had seen the cat had orbited through.

No. There was no way – he wasn’t going to be telling anyone. If others had told of this in the past, surely he wouldn’t have been surprised by the cat – it would have been in the real estate brochure.

“To hell with them. They can find it themselves,” he muttered, making his way back across the courtyard and inside.

* * *

To continue reading, click on the book cover below and go to ‘Look Inside’.